Organismic Integration Theory

This is part of my “Self-Determination Theory: Condensed” series, based on Chapter 8 of Deci & Ryan’s “Self-Determination Theory”. See this page for background, and links to other articles in this series.

The previous two chapters (here and here) covered Intrinsic Motivation. This chapter is focussed on Extrinsic Motivation. It explores what motivates people to participate in activities that are not necessarily intrinsically interesting or enjoyable.

A key question addressed in this chapter is whether, and how, extrinsic motivation can be autonomous.

Our analysis of Extrinsic Motivation begins by clarifying the concepts of “internalization” and “integration”

The Concept of Internalization

Internalization is defined as the process of taking in values, beliefs, or behavioural regulations from external sources, and transforming them into one’s own.

It is the internal psychological process that parallels the cultural process of socialization.

Socialization is only truly effective if behaviours or regulations are enacted even without ongoing enforcement. This is why socialization depends on internalization.

Like intrinsic motivation, internalization is a naturally occurring growth process, leading towards the end-point of integration.

Internalization involves both the individual aligning themselves with their social context, and also internal alignment of diverse values and regulations within the individual.

From an evolutionary perspective, internalization supports the harmonious and co-operative functioning of groups of humans. SDT believes that human development is inherently social.

However, internalization is not always positive, and does not always lead to harmony. Humans can (and often do) internalize prejudice and hate from the social contexts in which they are raised.

In modelling internalization, we need to consider both the process of internalization, and the content of what is internalized.

Internalization: All or None?

In chapter 7, we looked at ego-involvement, and saw that not all internally-generated motivation is autonomous, but can be deeply controlled. Our model of internalization must account for this.

It’s easy to find instances of diversity of the ways in which social values are internalized.

Consider, for example, religious observance by teenage children. Some children comply with their parents’ request to attend religious ceremonies due to feelings of guilt. Others will do so on the basis of full acceptance of the religion and its teachings. The same can happen with schooling, or any other demand that society places on its members. Extrinsically motivated behaviours may have a wide range of perceived loci of causality (PLOC), from E-PLOC to I-PLOC.

Organismic Integration Theory (OIT) was developed in order to model and explain this complex range of possibilities.

OIT posits that greater internalization of culturally valued regulations leads to a more internal PLOC, and to feelings of autonomy when carrying out regulated behaviours. Conversely, if regulations are less well-internalized, behaviours will have a more external PLOC, leading to half-hearted or dutiful behaviours, and feelings of conflict.

OIT sees internalization as a natural process, but one that only functions optimally when basic psychological needs are met.

In formal terms:

OIT Proposition I: The process of organismic integration inclines humans naturally to internalize extrinsic motivations that are endorsed by significant others. However, the process of internalization can function more versus less effectively, resulting in different degrees of internalization that are the basis for regulations that differ in perceived locus of causality and thus the extent to which they are autonomous.

A Model of Internalization and Integration

To transform values, beliefs or regulations that come from external sources into one’s own, requires integrating them with other values, beliefs or regulations that one already holds.

This is an active process that may require adjustments or refinements to either the new idea, or to previously held ideas.

In terms of the question of why we do this, SDT posits that internalization helps people to better meet their basic psychological needs (i.e. competence, relatedness and autonomy)…

Internalization and Need Satisfaction

Internalization is well aligned with competence needs. This begins with children modelling parents’ actions, and hoping to achieve similar outcomes. Later in life, internalization enables people to become effective members of their communities, enjoying both personal and social competence.

Internalization of family and cultural practices also supports a person’s sense of relatedness. Children most often model the behaviours of those they feel, or would like to feel, attached to.

Finally, as discussed above, internalization leads to greater feelings of autonomy when conducting external social practices - and therefore internalization also supports a person’s need for a sense of autonomy.

Internalization is a life-long process. Children internalize their family values, and then the values or rules of their school and community. Employees will internalize rules and values from the leaders at their place of work, and so on.

Types of Internalization and Regulation

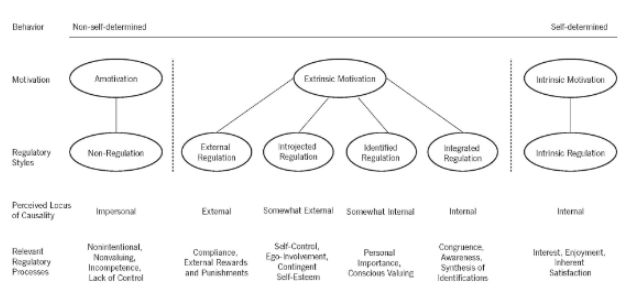

OIT identifies four types of extrinsic motivation, each corresponding to a different type of internalization.

External Regulation

A behaviour is externally regulated, if it is motivated by an external reward or punishment.

This is by far the most studied kind of extrinsic motivation. Indeed, for decades, operant theorists held that all behaviour depended on such external contingencies.

Operant psychologists have observed that certain procedures (e.g. certain reinforcement schedules) can result in behaviour continuing after the external contingencies are removed. However they do not recognize internalization as a possible explanation of such effects.

Within OIT, external regulation is behaviour where the reason for the behaviour is some external contingency. Typically the behaviour will persist as long as the person has an expectation (explicit or implicit) that the external contingency remains in effect. If the person believes that the external contingency is no longer in effect, the behaviour will not usually continue.

This type of regulation has an E-PLOC, and the behaviour is controlled.

External regulation can be a powerful motivator, but because the behaviour has not been internalized, it is unlikely to continue when the external contingencies are removed.

A further issue with external regulation is since the value of the behaviour lies in the reward (or in avoiding punishment), rather than the behaviour itself, behaviours will often be performed in a least-effort manner, without attention to quality.

Introjected Regulation

Unlike external regulation, introjected regulation operates internally to the person. It takes the form of an internal control that one “should” or “must” behave in a particular way.

Introjection tends to depend in part on internal feelings such as pride, guilt etc., but also in part on projections of the thoughts and actions of others (approval, disapproval etc.)

Introjection is powered by contingent feelings of worth, which may be dependent on the approval/disapproval of others, or on one’s own feelings of ego inflation and pride (or deflation and self-disparagement).

As we shall see in chapter 13, research has shown that introjection often derives from actual conditional regard (i.e. affection, praise or attention that is conditional on individual behaviour).

Various circumstances can lead to the intensification of introjection, to the point where a person is self-critical even in circumstances where no other person would think critically of them (“introjected perfectionism”). Competition and interpersonal comparisons seem to be key drivers for this effect - see also chapter 16.

Introjection is not merely a childhood phenomenon, or a stage of development. It can persist throughout life - indeed Loevinger (1976) put forward the view that this is the most typical way of being for most people.

Even when a person successfully conforms to introjected ideals, the resulting self-esteem is not deep or resilient, since it depends on specific conditions persisting (wealth, achievement, attractiveness etc.). Research has also shown that introjection drains vitality, and depletes ego.

Internal Control and the Self

Historically, “self-control” has been understood as a positive attribute: having self-control is a personal strength.

However, OIT identifies forms of self-control that are not self-directed, and therefore not autonomous. Introjection is a kind of partial internalization, that results in self-control, but does not represent full autonomy, or self-regulation.

A related concept, used by Kuhl (1996) is self-infiltration, whereby individuals adopt goals that someone else holds for them, as if they were their own. Introjection, is a similar process, but with values and behaviours, rather than goals.

The term introjection also appears in psychoanalytical writings (e.g. Schafer 1968). There are strong similarities with SDT’s conception of introjection at a phenomenological level. However, these theories differ from SDT in terms of how introjection arises.

Regulation Through Identification

Identification is the next step along the continuum of internalization (and hence autonomy), representing a more autonomous form of motivation than introjection, though not as fully autonomous as integration.

Identification amounts to a conscious endorsement of values and regulations. A person who identifies with the value and importance of a behaviour will see it as something personally important for them, and experience a more internal PLOC.

Note that, as conceived by SDT, the dynamic element here is the direct relationship between the individual, and the value or behaviour. This differs from theories such as Kelman (1958) or Schafer (1968) who understand attitude change as being driven by identification with particular other individuals, and see the acceptance of the attitude as resulting from a shift in that interpersonal identification.

Where identification falls short of full integration, is that the belief or value may not be wholly compatible with the various other attitudes and behaviours of the person.

We use the term compartmentalization (discussed in detail later) to refer to that manner in which a person may identify with multiple sets of values or behaviours, even if they are not completely consistent with each other.

Integration and Self-Determination

Integrated regulation is the fullest type of internalization, and is the basis for the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation.

Both identifications and introjects may become integrated. This is a process that requires self-reflection, and may require the adjustment of other previously held ideas, such that the new idea can form part of a consistent, coherent and integrated whole.

When values or behaviours are integrated, they can be endorsed wholeheartedly, without any internal conflict, and will be experienced as fully authentic.

Kazen (2003) introduced the concept of a self-compatibility check, which an identification must pass in order to be integrated.

A 2007 study looked at people trying to regulate their expression of prejudice. It assessed whether this regulation was introjected, identified, or integrated - and compared this with measures of prejudice exhibited, including both explicit and implicit prejudice. The study found that the more deeply internalized the regulation, the less prejudice was exhibited, on both explicit and implicit measures.

While integration is well understood in psychological terms, the biological underpinnings of integration are just beginning to be explored. Various studies from 2013 to 2016 involving brain scans have shown that

- the parts of the brain that seem to be central to our sense of self and our values, are indeed activated when we are in situations of inner conflict

- and further, that this activation is stronger in people who have higher basic needs satisfaction.

This suggests that enhanced support for basic needs can also support successful integration of identifications.

Internalization and Need Satisfaction

The process of internalization is a natural process, which itself provides support for basic needs satisfaction (i.e. relatedness, competence and autonomy), as follows.

- Acting in line with the norms of a social group promotes relatedness, and feelings of competence that arise from social efficacy.

- Internalization also results in a greater sense of autonomy.

- Integration offers not only the fullest experience of autonomy, but also eliminates potential sources of resentment and anxiety that may accompany introjected regulation. This resentment and anxiety can interfere with both relatedness, and effectiveness (i.e. competence).

Amotivation

Amotivation is another category of regulation, which is separate from the continuum of extrinsic motivation described above.

SDT sees amotivation as arising from two potential sources:

- The first is a lack of perceived competence. This may take the form of a belief that one cannot perform the required behaviours to achieve a particular outcome (“I can’t do what is being asked of me”), or alternatively a belief that a particular action will not in fact lead to a desired outcome (“I can do what is being asked of me, but it won’t have any impact”).

- The second is related to autonomy: indifference about an activity or related outcomes. This may be thoughtfully considered indifference or disapproval, or may simply be due to a lack of information or awareness of the potential value of acting.

An important difference between these two types of amotivation is that the latter can potentially be accompanied by a strong sense of autonomy. That is not true in the former case.

A 2004 study looked at the reasons that unemployed people had for not searching for a job (a form of amotivation).

Where individuals had autonomous reasons for not searching, this was associated with more pleasant job search experiences, and greater life satisfaction, which was not the case for individual with competence-based reasons for not searching.

Amotivation, therefore, is not always the result of helplessness, or a lack of efficacy, but can be an autonomous, self-endorsed absence of motivation to act.

Indeed there are plenty of examples of behaviours for which it is healthy and pro-social to have this kind of autonomous amotivation. Examples might include amotivation towards physically harming others, or damaging property.

The Continuum of Relative Autonomy

Having introduced the various concepts above, we are now in a position to present another formal proposition of OIT:

OIT Proposition II: Internalization of extrinsic motivation can be described in terms of a continuum that spans from relatively heteronomous or controlled regulation to relatively autonomous self-regulation. External regulation describes extrinsic motivation that remains dependent on external controls; introjected regulation describes extrinsic motivation that is based on internal controls involving affective and self-esteem contingencies; regulation through identification describes extrinsic motivation that has been accepted as personally valuable and important; and integrated regulation describes extrinsic motivation that is fully self-endorsed and has been well assimilated with other identifications, values and needs. Regulations that lie further along this continuum from external towards integrated are more fully internalized, and the resulting behaviours are more autonomous.

The following diagram summarises all the different forms of behavioural regulation, including intrinsic motivation, the various forms of extrinsic motivation, and amotivation.

Assessment of an Autonomy Continuum

The presentation of a continuum in OIT Proposition II leads to a number of predictions that are empirically testable.

One particular implication of the idea that the various regulatory styles form a continuum, is that correlations between these regulatory styles should form a quasi-simplex pattern, meaning that adjacent styles on the continuum should be positively correlated, with correlations weakening (and eventually becoming strongly negative) the greater the distance between two regulatory styles on the continuum.

This quasi-simplex pattern has been observed in many dozens of studies since 1989, which have involved both children and adults.

Other forms of analysis that have supported the idea of a continuum include small space analysis (a derivative of multdimensional scaling) and a bifactor-ESEM framework [explaining the technicalities of these types of statistical analysis is beyond the scope of this article].

Most recently, a 2016 paper using samples from the United States and Russia, and a combination of all these techniques, reported robust evidence for an underlying continuum of autonomy.

Predictive Indexes and Profiles

Studying the effects of different types of motivation is complicated by the fact that most of the time, there are multiple regulatory styles in play at the same time.

One commonly-used approach is to compute a single Relative Autonomy Index (RAI) from the weights of each regulatory style. For example an RAI could be computed as:

(-2 x External) + (-1 x Introjected) + (1x Identified) + (2 x Intrinsic)

Indices like this have been found to be predictive of a range of outcomes, from behavioural persistence to customer loyalty. However such measures risk masking specific important interactions between regulatory styles.

Another approach is to compute values on two independent sub-scales: autonomy and controlled. Again, this has been found to have strong predictive power.

A further approach known as latent profile analysis takes into account multiple regulatory styles, mapping data into a number of sub-groups, each of which clusters around a particular “fingerprint” of regulatory styles (a “latent profile”). A 2016 study has shown that such an approach using 4 regulatory styles (external, introjected, identified & intrinsic) provides a more differentiated and meaningful description of motivation, compared to profiling that reduces the data to just one or two factors.

Each of the above modelling approaches can be useful. Which one is optimal will vary depending on the context, and the specific research questions being asked.

Intrinsic Motivation, Extrinsic Motivation, and Autonomy

Autonomous behaviour in Infants and young children primarily consists of intrinsically motivated behaviour. As they mature and approach adulthood, more of their autonomous behaviour results from internalized regulation.

Multiple studies have shown a decrease in intrinsic motivation, and an increase in extrinsic motivation, over children’s school years.

Multiple factors contribute to this, and it is not easy to separate out the relative importance of these factors:

- In part this may be due to the use of of controlling strategies used within schools (which, as covered in chapters 6 & 7 would be expected to undermine intrinsic motivation)

- It could also be due to a shift in care-giving that begins to focus more on structures and prompts that encourage the internalization of key social values.

- It may simply be a natural process that occurs as children mature and become more interested in participating competently within the adult social world.

This next section looks more closely at internalization, and what supports (or inhibits) the internalization of particular ideas, behaviours or practises.

Intrinsic Motivation and Internalized Regulation

Integrated regulation is a highly autonomous form of behaviour, but it is not the same as intrinsic motivation, as it remains fundamentally instrumental: these activities are undertaken in support of goals or values, not because they are inherently interesting and enjoyable.

While this distinction can be important, some similarities are also important.

- Commonly, it is the level of autonomy experienced that is most functionally significant. This level of autonomy can be just as high with integrated regulation, as with intrinsic motivation.

- Both intrinsic motivation and integrated regulation are facilitated by supports for the three basic psychological needs.

One important difference between intrinsic motivation and integrated regulation is the person’s perspective in terms of time. With intrinsic motivation, although the activity may lead to future benefits such as increased competence, this is not the aim. Whereas because integrated regulation is always instrumental, there is inherently a focus on future goals or outcomes.

In order to feel positively inclined towards an activity that is not inherently enjoyable, it is necessary to bring the future to mind. Mindfulness of these future outcomes provides an essential support for identified regulation of an activity.

Another important difference is that intrinsically motivated activities are typically spontaneous, whereas integrated regulation often follows a process of reflection on both goals and values, and the meaning, value or utility of an activity. A 2016 study showed that a higher-level of reflection on why one was pursuing a goal (setting it into broader goals and life context), led to a greater sense of both meaning and autonomy.

The Internalization Continuum and Psychological Development

The internalization continuum presented above represents increasing levels of autonomy, but does not represent a process of internalization - i.e. the internalization of a particular behaviour does not necessarily proceed from left to right.

Beliefs or behaviours can be integrated without ever being introjected, and young children can fully internalize certain regulations at an early age (once they have the capacity for self-regulation).

However, there are some developmental issues that are relevant. In particular, to authentically value a particular behaviour may require a level of context and understanding that a child does not yet have. In this case, the regulation could not be identified or integrated, and could only be external or introjected.

Even when a regulation is externally triggered, it can still be fully internalized quickly. For example, when a country passes a law mandating the wearing of seatbelts, a person can immediately internalize the practice and comply with it, immediately seeing the value in the practice.

People can also transition backwards on the continuum as well as forwards. One study of children in 4th grade to 6th grade found that they became less autonomous in their regulation of their schoolwork, when exposed to teachers who used controlling practices.

Internalization and Compartmentalization

One key characteristic of the continuum of internalization is that the more internalized regulations are, the more they cohere with other internalized regulations, and with the person’s broader needs and values.

Introjects held by people are often rigid and inflexible, and acted on without much consideration. They are also often inconsistent, sometimes with the person not even aware of the inconsistency.

Identified regulations are typically more considered, which leads to them being more flexible. However, some people have strong identifications that are compartmentalized. In these cases, the person tends to hold the identification very rigidly and to be defensive with regard to it. The strong identification is isolated from the person’s other identifications and ideas, and the person remains closed to any feedback concerning the identification.

Compartmentalized Identifications

This distinction between open identifications (which are not held defensively) and closed identifications (which are consciously held and vigorously defended) is important for explaining some aspects of human behaviour.

OIT holds that there is an inherent tendency to integrate, unless there is something thwarting this natural process.

However, some identifications are not easily integrated, due to conflicts with other identifications. If they are not to be dropped or modified, they must be closed, i.e. isolated from other aspects of experience.

A 2012 series of studies found that participants with controlling, homophobic parents (especially fathers) had a greater discrepancy between the sexual orientation that they self-reported, and that which was implicitly assessed.

The OIT interpretation of this study is that participants who showed this discrepancy had a closed, or compartmentalized, identification with heterosexuality, which they held on to and defended, in spite of the fact that it conflicted with their experience.

These participants were further shown to be more likely to act with bias, or even advocate aggression, towards gays and lesbians. This was seen as evidence of a defensive response to a perceived threat to this compartmentalized identification.

OIT holds that while our natural tendency is towards integration, coherence and internal consistency (since this gives us the most support for meeting our basic psychological needs), under adverse conditions, alternative compensating mechanisms can emerge - and compartmentalizing of identifications are one such mechanism.

Strategies of Socialization and Internalization

Internalization of the cultural norms in which a person is raised is a naturally occurring process, which serves that person’s needs for relatedness, allows them to experience competence, and supports their need for autonomy.

SDT asserts that extrinsic motivations and values are more fully internalized when people live in need-supportive environments.

Research in 2007 showed that individuals whose parents had been more autonomy-supportive when transmitting their values

- had more autonomous motivation for those values

- perceived greater congruence between their own values and their parents’

- had better overall psychological wellness.

Need Support and Internalization

The process of internalization is a natural part of human growth, but does still need a level of support. In broad terms, autonomy, competence and relatedness are each beneficial for internalization, but there are important specific relationships between individual needs, and particular styles of regulation.

-

All forms of behavioural regulation, even including external regulation require at least some minimal level of competence.

-

Introjection requires more than just competence. It also requires a level of relatedness: one must care what other people think.

-

Identification and integration require a level of autonomy, in order to “make an idea one’s own”.

In this context, we present the 3rd formal proposition of OIT:

OIT Proposition III: Supports for the basic needs for competence, relatedness and autonomy facilitate the internalization and integration of non-intrinsically motivated behaviours. To the extent that the context is controlling, and/or relatedness and competence needs are thwarted, internalization, and particularly identification or integrated regulation, will be less likely.

This proposition is relevant both at a social psychological level (i.e. short-term, and with regard to a specific behaviour or value) and at a developmental level (i.e. longer term, and with regard to the broader development of autonomous self-regulation).

Research on Internalization and the Social Context

There is much research to support OIT Proposition III, some of which will be reviewed in later chapters on parenting and development.

For now, we look at just a few examples of such studies. First, some field studies:

-

A 1989 study showed that students’ perceptions of their teachers’ autonomy support resulted in more identified academic regulation.

-

Another 1989 study assessed how parents motivated their children to perform homework and household chores, measuring their involvement (time spent with the children), the structure they provided (clear guidelines and expectations), and how autonomy-supportive they were.

- Parental autonomy support was found to predict autonomy with schoolwork (integrated regulation and intrinsic motivation), adjustment to the classroom (as rated by the teacher), and academic scores.

- Parental involvement was found to predict academic scores, and understanding of what influences school outcomes.

Parents rated as controlling were typically very concerned with their children’s outcomes. However their attempts to control their children seem to have undermined the very academic outcomes that they were seeking.

-

A 2006 study looking at students’ motivation to go to college, found that students’ perceptions of the need support they received from their parents was predictive of their autonomous self-regulation for pursuing further education.

Similar results have also been seen in laboratory studies.

In a 1994 study, participants were asked to perform a boring task of watching a computer screen and pressing a button as quickly as possible each time dots flashed on the screen. The study showed that free-choice persistence with this dull task was independently boosted by:

-

providing a meaningful rationale for the activity

-

acknowledging their feelings (specifically that the task was boring)

-

providing instructions that emphasized choice and minimized control (vs. a more controlling and directive set of instructions)

Nevertheless, there was some free-choice persistence seen even for some participants with either zero or one of these supports. Further analysis showed that where two or more of these supports were provided, there was a strong correlation between free-choice persistence and self-reports of perceived choice, utility and enjoyment of the task (suggesting integrated regulation). Whereas when there were zero or one supports, there was a weak or negative correlation between these self-reported factors and free-choice persistence (suggesting that the free-choice persistence that did occur was introjected, rather than integrated).

There is clear, longstanding evidence that some level of internalization can occur even under controlling conditions (e.g. reinforcement schedules from operant psychology, as mentioned earlier). The evidence from this study (and others) that such internalization is likely to take the form of introjection (and therefore be less congruent and authentic, and less likely to persist over time) is an important insight of SDT.

A 2011 experiment looked at the effects of various messages on the regulation of prejudice. It found that autonomy-supportive messages reduced prejudice, but controlling anti-prejudice messages actually increased prejudice vs. a control in which no message was provided. A similar result was found when a uniform anti-prejudice message was provided to participants, but preceded by priming procedures that created either an autonomy-supportive orientation, or a controlling orientation. The autonomy-supportive priming reduced prejudice, while the controlling priming increased prejudice.

In summary, in the context of controlling factors, people are less likely to internalize values. And what internalization does occur is likely to take the form of introjection, rather than identification.

Autonomy Support and Internalization

There are many further studies that have shown how autonomy support can boost both internalization, and the subsequent autonomous motivation that results from it. These are just a few of those studies.

- In a 2007 study, multicultural students in Canada were found to have more fully internalized both their host and heritage cultures, if they experienced their parents as more autonomy-supportive.

- A 2002 study looked at doctors counselling patients to stop smoking. Greater autonomy-support from the doctors led to greater internalization of the value of stopping smoking (based on post-counselling interviews with the patients).

- A 1996 study at a weight loss clinic found that perceptions of autonomy support from staff at the clinic predicted higher patient autonomous motivation, higher attendance, greater weight loss over the 6 months of the program, and better maintenance of weight loss at a 2-year follow-up.

This final point about long-term maintenance is crucial, because SDT theorizes that it is precisely through internalization (i.e. truly accepting the value of a healthier diet and regular exercise) that regulation is maintained in the long-term.

A 2012 meta-analysis of 184 independent studies found that autonomy support strongly predicted autonomous motivation for changes in behaviour that would benefit health.

These, and many other studies, show us that autonomy support is hugely important for the internalization of social values. Unfortunately, in today’s society, such conditions are frequently not provided, which results in sub-optimal internalization, with values and regulations never full integrated.

The Consequences of Internalization

Results show that fuller internalization results in greater behavioural persistence, higher quality performance, and more positive psychological experiences.

Integrated self-regulation is also likely to be more congruent with basic psychological needs and thereby enhance wellbeing.

This leads to the two final formal propositions of OIT:

OIT Proposition IV: To the degree that people’s behaviour is regulated through more autonomous or integrated forms of internalization, they will display greater behavioural persistence at activities, a higher quality of behaviour, and more effective performance, especially for more difficult or complex actions.

OIT Proposition V: To the degree that people’s behaviour is regulated through more integrated forms of internalization, they will have more positive experiences and greater psychological health and well-being.

A large number of studies, employing a wide range of different methods, have provided evidence for these propositions.

In addition to studies in the context of school-related activities mentioned above, which showed both the positive benefits of integrated regulation, and the negative consequences of introjected regulation, studies have shown similar results in the fields of religion, health care, aging and sport (among many others).

We look at a few of these studies here, although the later applied chapters will cover many more.

Internalization, Behavioural Persistence, and Goal Attainment

A 1996 study of students’ New Years Resolutions found that those who had stronger identified or intrinsic reasons (rather than external or introjected reasons) were more likely to have maintained their resolutions two months later.

A couple of studies of pro-environmental behaviours (in 1997 and 1999) found that people with more autonomous forms of motivation were more persistent in carrying out behaviours. This relationship became stronger, the more difficult the behaviour was to carry out.

A 1995 study of swimmers found that autonomy support from coaches predicted autonomous motivation on the part of the swimmers, and a 2001 study of athletes found that self-determined forms of motivation were strong predictors of persistence over an extended period, while controlled forms of motivation (including introjection) were weak predictors of persistence, and this weakness increased with the passing of time.

Other studies have shown similar effects in personal dental care, and studying music.

A slightly different pattern has been observed in studying treatment plans for alcoholism and opiate dependence. In these contexts, it appears that introjected regulation is also strongly predictive for persistence. External regulation, however, did not have any positive effects. So, specifically in the context of heavy addictions, it seems that introjected regulation can be an important factor for positive outcomes - an effect that has not been seen in other contexts.

Some studies related to how people form opinions highlighted some other differences in the dynamics of different regulatory styles.

Those with introjected beliefs were found to be vulnerable to persuasion (particularly by attractive communicators), and reliant on the opinions of significant others, whereas those with identified beliefs tended to actively seek out information for themselves, form their own views, and be more resistant to persuasion. These effects were seen in a 1996 study on voting behaviours, and a 2001 study on environmental attitudes.

A follow-up study of political behaviour found that in this domain, identified regulation may in fact be superior to intrinsic motivation. Those with high identification, who had internalized the importance of politics were more likely to vote, had stronger beliefs, and felt more positive if their side won, as compared to those who followed politics out of intrinsic interest.

The above studies were selected in particular in order to highlight two key points:

- first, that there are distinct types of motivation, each of which has distinct phenomenology, and a different relationship to outcomes.

- second, that multiple different types of motivation often co-occur, resulting in the potential for many different configurations of motivations, across domains and across individuals.

The rich taxonomy of motivation offered by OIT allows for a much more sophisticated model of motivation than the unitary (or single-factor) view of motivation embraced by many other theories.

Self-Concordance

The term self-concordance was introduced by Sheldon and Elliot in 1999 to refer to the level of autonomy of peoples’ personal goals.

Self-concordance is a measure of a person’s overall autonomy with regard to their goals, rather than a measure of a person’s relationship to a specific individual belief, goal or value.

Self-concordance has been found to be predictive of sustained effort and also overall well-being due to greater overall need satisfaction.

Sheldon and Elliot have talked about an upward spiral whereby self-concordance enables well-being, which in turn supports greater autonomy, and greater self-concordance.

Studies in 2002 identified two factors were important for goal attainment:

- Implementation intentions (i.e. specific plans about when, where and how to proceed with pursuit of the goal)

- self-concordance.

A follow-up study on New Year’s Resolutions showed that in the absence of self-concordance, implementation intentions alone were insufficient to deliver progress on the resolution.

Internalization, Relative Autonomy, and Well-Being

Finally, we review some of the evidence that exists for OIT Proposition V, which relates fuller internalization to overall psychological well-being.

A 1993 study of religious values and behaviour found that identified regulation was associated with various indicators of well-being, while introjected regulation was associated with anxiety, depression and somatization (the expression of psychological stress through physical symptoms).

A 1989 study of elderly people’s regulation across six different life domains found autonomous motivation was related to self-esteem, finding meaning in life, and being active, while non-autonomous motivation was associated with depression.

An important point to note about the model of internalization presented in OIT is that it is neutral with regard to cultural contexts. A good example of this is with the issue of duties or obligations to one’s family. In Western cultures these may be characterized as non-autonomous. However in Hindu culture, for example, these concepts of duty are often more fully internalized, and therefore may be experienced as autonomous. A 2011 study showed that being expected to help friends and family was associated with identification, a sense of satisfaction and choice, among Indians, but not among Americans.

Concluding Comments

In infancy and early childhood, intrinsic motivation is dominant, but as demands are placed on the child to conform to social norms, extrinsic motivation becomes more important.

In most societies, extrinsic motivation becomes the dominant motivating force for most of one’s adult life (a possible exception being retirement in Western cultures, where intrinsic motivation can make a significant return).

Internalization of extrinsic regulations is of crucial importance for both effectiveness and well-being.

This internalization can be facilitated by support for individuals’ basic psychological needs: competence, relatedness and autonomy.

Relatedness is essential for internalization to occur at all. However, when behaviours are demanded of a person before they are developmentally ready, this will typically lead to either introjection or amotivation. Successful identification and integration require both competence, and autonomy.

In some social contexts, inflexible attitudes mean that individuals must choose between autonomy and relatedness. This frequently leads to introjection, which amounts to a sacrificing of autonomy for the sake of relatedness, but is ultimately harmful for well-being.

There is a strong body of evidence showing that more fully internalized forms of regulation lead to individuals engaging in behaviours or activities more reliably and effectively - and also lead to better overall psychological well-being.

Key Concepts from this Chapter

Extrinsic Motivation: Motivation that derives from the instrumental effects of a task or activity, rather than the inherent interest or enjoyment that the task or activity provides.

Internalization: The process of taking in values, beliefs, or behavioural regulations from external sources, and transforming them into one’s own.

OIT Proposition I: Internalization of extrinsic motivations endorsed by significant others is a natural growth process in humans, which may be supported or thwarted by the surrounding social context.

Organismic Integration Theory differentiates 4 types of Extrinsic Motivation:

External Regulation is driven by external factors (consequences, rewards, threats etc.)

Introjected Regulation operates internally to the person, but takes the form of an internal control that one “should” or “must” behave in a particular way.

Identified Regulation occurs when a person consciously endorses a value or regulation.

Integrated Regulation occurs when an identified regulation has been accepted in a way that is fully consistent with other values or ideas held by the person.

Amotivation: A motivational concept distinct from Intrinsic or Extrinsic Motivation. It reflects a strong motivation not to perform a particular task or activity. It may stem from a perceived lack of competence, or from a lack of value of the outcome that the task or activity is expected to lead to.

OIT Proposition II: The 4 types of Extrinsic Motivation form a continuum, from the least autonomous to the most autonomous forms of extrinsic motivation.

Compartmentalized Identification: An identification is compartmentalized, when it is held very rigidly, and the person remains closed to any feedback concerning the identification. Compartmentalized identifications cannot be integrated.

OIT Proposition III: Internalization is supported (in distinctive ways) by the three basic psychological needs: competence, relatedness and autonomy.

OIT Proposition IV: Greater levels of internalization lead to greater behavioural persistence, and a higher quality of behaviour.

OIT Proposition V: Greater levels of internalization, lead to improved psychological health and well-being.

Self-concordance: An overall measure of a person’s autonomy with regard to their goals. The extent to which their self-regulation is integrated.