Cognitive Evaluation Theory Part 1

This is part of my “Self-Determination Theory: Condensed” series, based on Chapter 6 of Deci & Ryan’s “Self-Determination Theory”. See this page for background, and links to other articles in this series.

The Effects of Rewards, Feedback and Other External Events on Intrinsic Motivation

Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET) is the first of SDT’s 6 mini-theories, and focuses exclusively on intrinsic motivation.

Intrinsic Motivation is motivation for an activity that is done for the inherent satisfaction gained from the activity. It can be contrasted with Extrinsic Motivation, where the motivation for the activity arises from the effects that it is anticipated will result from the activity.

SDT began with the study of Intrinsic Motivation

The study of Intrinsic Motivation is where SDT began. It represents just one part of human motivation, but study in this area led to some paradigm-shifting results, which were fundamental to the overall genesis of SDT.

Most notable was the observation that although intrinsic motivation is widespread, it is readily diminished in certain contexts (for some conspicuous examples, consider what can be observed in some classrooms, workplaces and gyms). Early SDT research was motivated to understand which social conditions tend to support intrinsic motivation, and which tend to thwart it.

This is now a well-studied area, with hundreds of studies completed over four decades.

SDT understands intrinsic motivation as a naturally emerging propensity in humans, and so CET is not looking for the cause of intrinsic motivation, but rather the social factors that support or thwart its emergence.

Overview of CET claims

At the very highest level, CET asserts that when a person has negative feelings in terms of either their autonomy, or their competence, their intrinsic motivation will be reduced. And conversely, when a person has positive experiences of autonomy and/or competence, this will tend to increase their intrinsic motivation.

Furthermore, both autonomy and competence are necessary for intrinsic motivation to be sustained. One or the other, by itself, is not enough.

Additionally, relatedness also plays a role in supporting intrinsic motivation, particularly for activities that have a social element.

Extrinsic Rewards and Intrinsic Motivation: The Early Experiments

Early Studies of Tangible Rewards

At the beginnings of SDT, the relationship between externally administered rewards and intrinsic motivation was a controversial area of study. The discovery that in certain conditions, rewards might actually diminish certain forms of motivation was antithetical to traditional behaviourists and economists.

in 1971 Deci began with the research question: “What would happen to a person’s subsequent intrinsic motivation for an interesting activity if the person were given a monetary reward for doing it?”

Underlying this specific question was the more abstract question as to whether extrinsic and intrinsic motivation were simply additive, or had some more complex interrelation.

Operant psychology, the dominant paradigm in psychology at the time, held that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation would be additive (i.e. extrinsic motivation and intrinsic motivation could be added together without impacting each other).

In order to measure “intrinsic motivation” Deci developed the “free choice paradigm”. The idea was to measure the amount of time that participants spend on an activity after some experimental intervention, when they are alone, free to choose what to do, and with no external incentives or evaluations. This time duration is interpreted as a measure of intrinsic motivation.

Further insights regarding intrinsic motivation can also be gained through self-reports (e.g. Ryan’s Intrinsic Motivation Inventory, 1983).

In Deci’s 1971 study, which involved a puzzle solving activity, it was found that participants who were paid $1 per puzzle solved had less subsequent intrinsic motivation to solve puzzles, than those who were unpaid. Similar effects were soon replicated elsewhere.

A further study showed that where participants were paid simply for showing up for the experiment (rather than per puzzle solved), the payments had no negative impact on their intrinsic motivation for puzzle solving.

The results of these studies caused an outcry among behaviourists, but multiple studies confirmed the effect. A similar effect was found among pre-schoolers when the reward consisted of a non-monetary “good player award”. However, a further (1973) study found that this effect only occurred where the pre-schoolers were told about the award in advance of the activity - when the reward came unexpectedly after the activity, there was no negative impact on intrinsic motivation.

A study by Ross in 1975 found a difference between children being told they would receive an (unspecified) prize for playing a drum, and those who were told they would receive a prize that was in a box in front of them. Only for the latter group was intrinsic motivation to play with the drum diminished.

Therefore it appears that the salience of the rewards (i.e. to what extent they are at the forefront of awareness) is also significant in terms of the tendency of rewards to undermine intrinsic motivation.

Overall, it appears that to undermine intrinsic motivation, rewards must be introduced before the activity begins, must be salient, and must be contingent. It is notable that these attributes are all evident when rewards are used in a controlling manner.

Perceived Locus of Causality

The concept of a “Perceived Locus of Causality” (PLOC) comes from de Charms, 1968, and has been used by Deci and Ryan to explain the results described above.

An intentional behaviour can be intrinsically motivated, in which case it has an internal perceived locus of causality (I-PLOC), or extrinsically motivated, in which case it has an external perceived locus of causality (E-PLOC).

Behaviours with an I-PLOC are experienced as autonomous, and those with an E-PLOC are experienced as controlled (or non-autonomous).

In order to explain the results described earlier, Deci and Ryan (19080, 1985) theorized that introducing rewards could shift the PLOC from an I-PLOC to an E-PLOC, thereby diminishing the subject’s experience of autonomy.

However it is possible to provide rewards in a way that does not undermine autonomy, as seen in some of the examples above. The theory of CET was constructed to help to explain the differences.

Early Studies of Positive Feedback: Competence Satisfaction and Intrinsic Motivation

A second parallel branch of research explored the impact of non-tangible rewards (or “verbal rewards”) on intrinsic motivation.

There are many different kinds of verbal rewards, including telling people they are good at the activity, telling them they are good for doing the activity, or telling them that they did better than others at the activity. Each has a distinct effect.

Early studies (1971 to 1975) showed that competence-focussed positive feedback enhanced subsequent intrinsic motivation. Deci and Ryan theorized (1) that the feedback enhanced the participants’ sense of competence, and (2) that since the feedback was unexpected, the participants’ had no sense of having performed the task in order to receive praise, so they also had an I-PLOC rather than an E-PLOC. Both of these mechanisms were thought to have led to the increase in intrinsic motivation.

In 1975, Smith tested the idea that some forms of praise might be experienced as evaluations, pressure, or control, prompting an E-PLOC. His study showed that when people were told in advance that they would be evaluated on a task, this reduced their intrinsic motivation, even though the feedback was positive.

Various further studies have shown that if when positive feedback is presented in a way that might be perceived to be controlling, it tends to diminish intrinsic motivation, rather than enhancing it.

Autonomy, Competence and CET

The various studies described above led to the formulation of the first two formal propositions of CET

CET Proposition I: External events relevant to the initiation or regulation of behaviour will affect a person’s intrinsic motivation to the extent that they influence the perceived locus of causality for the behaviour. Events that promote a more external perceived locus of causality or have a functional significance of control will thwart autonomy and undermine intrinsic motivation, whereas those that promote a more internal perceived locus of causality will increase feelings of autonomy and enhance intrinsic motivation.

CET Proposition II: External events will also affect a person’s intrinsic motivation for an activity, to the extent that the events influence the person’s perceived competence at the activity. Events that promote greater perceived competence enhance intrinsic motivation by satisfying the person’s need for competence. Events that meaningfully diminish perceived competence undermine intrinsic motivation.

Crucial to both of the above, is that a person’s experience of their situation impacts the effect on their intrinsic motivation. Therefore it becomes important to understand the functional significance for the recipient of a particular external stimulus.

The same external stimulus could be experienced as controlling by one person, yet as competence affirming by another.

This leads to:

CET Proposition III: External events relevant to the initiation and regulation of behaviour have three aspects, each with a functional significance. The informational aspect, which conveys information about self-determined competence, facilitates an internal perceived locus of causality and perceived competence, thus supporting intrinsic motivation. The controlling aspect, which pressures people to think, feel, or behave in particular ways, facilitates an external perceived locus of causality, thereby diminishing intrinsic motivation. The amotivating aspect, which signifies incompetence to obtain outcomes and/or a lack of value for them, undermines both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and promotes amotivation. The relative salience of these three aspects for the person, which can be influenced by factors in the interpersonal context and in the person, determines the functional significance of the event, and thus its impact on intrinsic motivation.

To predict the impact of a particular reward, one must consider how the reward is likely to be interpreted in each of these three aspects.

When a reward has multiple aspects that may be in conflict, the relative salience of different aspects becomes relevant to the impact that the reward is likely to have.

One interesting example where a reward did not seem to undermine intrinsic motivation was in a 2008 study which showed that rewarding third-grade children’s reading with books actually increased their intrinsic motivation for reading. In this case, the most salient aspect of the reward seems to have been to convey the value of reading to the children, and this appears to have outweighed the controlling aspect of the reward.

Reward Contingencies: For What Are Rewards Being Given?

There are many different ways in which rewards can be administered.

In 1983, Ryan created the following taxonomy of reward types:

- Task-noncontingent - Reward given simply for being present

- Task-contingent - Reward depends on how the task is performed, which includes two sub-types:

- Engagement-contingent - Reward given for spending time engaged on the activity

- Completion-contingent - Reward given for completing an activity (possibly within a time-limit)

- Performance-contingent - Reward given for reaching a particular performance target

- Competitively-contingent - Reward given for doing better than other participants (e.g. winning a contest)

The effects of different types of rewards have been found to be as one might expect…

- Task-noncontingent rewards do not undermine intrinsic motivation, while task-contingent rewards do.

- Within task-contingent rewards, there was found to be little difference between engagement-contingent and completion-contingent rewards. While completion-contingent rewards might be thought to signal competence affirmation, they are also perceived as even more controlling, and these effects seem to even out.

- With performance-contingent rewards, there are both controlling and competence-affirming aspects. However studies have shown that performance-contingent rewards undermine intrinsic motivation, when compared to the equivalent positive feedback (without reward), and even when compared to a scenario with no feedback/reward.

- Also note that in these lab studies, all the participants received the reward, which is the “best case” in terms of motivation. There have also been studies that have looked at the “losers” in performance-contingent reward scenarios. Perhaps unsurprisingly, such studies have shown a very large undermining of intrinsic motivation in these conditions.

- The effects of competitively-contingent rewards are broadly similar to those of performance-contingent rewards.

Meta-Analysis of Reward Effects

There have been many attacks from behaviourists against the idea that rewards diminish intrinsic motivation, but the evidence in favour of this effect continues to mount.

CET does not deny the fact that rewards can control immediate behaviour - the question concerns the effects on subsequent motivation and behaviour.

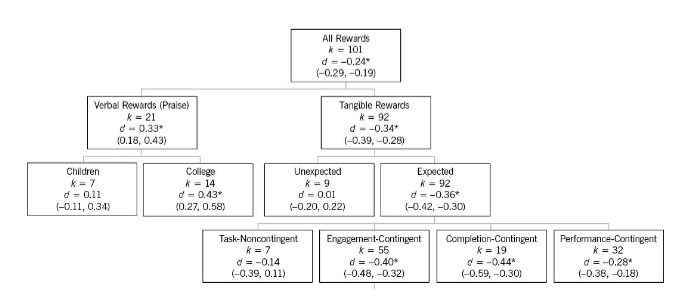

In 1999 Deci created a comprehensive meta-analysis of relevant studies in this area. With rewards grouped into various categories, the overall effects on intrinsic motivation were as follows:

| Reward type | # studies | Impact on intrinsic motivation | 95% confidence intervals |

|---|---|---|---|

| All rewards | 101 | -0.24 | -0.29, -0.19 |

| Verbal rewards (praise) | 21 | 0.33 | 0.18, 0.43 |

| Verbal rewards (praise) - children | 7 | 0.11 | -0.11, 0.34 |

| Verbal rewards (praise) - college students | 14 | 0.43 | 0.27, 0.58 |

| Tangible rewards | 92 | -0.34 | -0.39, -0.28 |

| Unexpected tangible rewards | 9 | 0.01 | -0.20, 0.22 |

| Expected tangible rewards | 92 | -0.36 | -0.42, -0.30 |

| Task-noncontingent expected rewards | 7 | -0.14 | -0.39, 0.11 |

| Engagement-contingent expected rewards | 55 | -0.40 | -0.48, -0.32 |

| Completion-contingent expected rewards | 19 | -0.44 | -0.59, -0.30 |

| Performance-contingent expected rewards | 32 | -0.28 | -0.38, -0.18 |

The same data in diagrammatic form:

Some commentary on this data…

Positive feedback (verbal rewards)

According to CET, positive feedback may have an informational aspect (positive for intrinsic motivation) or a controlling aspect (negative for intrinsic motivation).

The observed difference between data for children vs. college students is likely to be because children are more likely to experience the positive feedback as controlling, while college students are more likely to experience it as informational (Causality Orientation Theory, in chapter 9, will look at why this might be).

Tangible Rewards

The data aligns with the predictions of CET, both in the generally negative impact of tangible rewards on intrinsic motivation, and also in terms of unexpected rewards being broadly neutral, while expected rewards are strongly negative.

Not shown in the above data, analysis of school-aged children vs. college students also showed that the negative effects were strongest for school-aged children, particularly in the case of engagement-contingent rewards. Again, this probably reflects the fact that school-aged children are more likely to experience engagement-contingent rewards as controlling.

This is highly relevant to those working with school children, since both parents and teachers commonly rely on tangible rewards as a motivational strategy for children - the data suggests that this is a misguided approach.

Performance Contingent Rewards

Performance Contingent rewards merit some additional comments.

There were four different approaches taken in performance-contingent reward experiments, grouped as follows:

- participants getting the maximum possible reward, with the control group getting no reward & no feedback

- participants getting various different rewards, with the control group getting no reward & no feedback

- participants getting the maximum possible reward, and the control group getting the same positive feedback, but no reward

- participants getting rewards that indicated poor performance (e.g. their lowest tier of available reward), and the control group getting the same negative feedback, but no reward.

Category 2 showed the strongest undermining effect (in fact this was the strongest undermining effect of all reward categories in the meta-analysis)

Categories 1 & 3 showed significant, but weaker, undermining effects - but it’s important to note that these studies are not representative of the real world, where not all participants will receive the maximum possible reward.

Category 4 did not show a significant undermining effect (but there were only 3 studies in this category). One explanation of the results, consistent with CET, is that the participants intrinsic motivation has been sufficiently undermined by the negative feedback, that there is little left to be undermined by the reward itself.

Longevity of Effects

The same 1999 Deci meta-analysis also compared the undermining effect over various different time periods (up to a few days). No significant effect on the undermining effect was detected, suggesting that the undermining effect is not simply a transitory phenomenon that quickly dissipates.

Assessment of Intrinsic Motivation

Another important point highlighted in the meta-analysis is that across the studies, there was only modest correlation between self-report measures of intrinsic motivation, and the free-choice measure (i.e. how long the participant actually chose to spend on the activity, in a subsequent free-choice situation).

The free-choice measure consistently showed more significant undermining of intrinsic motivation than the self-report measure.

Which has greater validity?

Both have potential issues

- For the self-report measure, participants are asked how interesting or enjoyable they find the activity. They may confuse their enjoyment of the reward with the enjoyment of the task itself.

- For the free-choice measure, under some circumstances participants may return to the activity for reasons other than intrinsic motivation (for example, to assuage concerns about their performance, in the face of ambiguous feedback). When a manipulation stimulates ego involvement (see later chapter), this kind of effect may be significant, but it is not believed to be significant in the kind of experiments that were analyzed in the meta-analysis. In any case, if the effect did exist, it would led to an underestimate rather than an overestimate, of any undermining of intrinsic motivation.

The net of the above is that there are reasons to consider the free-choice measure to be the more valid measure of intrinsic motivation, and the extent to which it has been undermined (or enhanced) by rewards.

Comparison to previous Meta-Analyses

Several previous (less comprehensive) meta-analyses were completed prior to 1999.

Rummel and Feinberg (1988), Wiersma (1992) and Tang and Hall (1995) all conducted meta-analyses that provided support for CET.

Cameron and Pierce (1994) conducted a meta-analysis of reward effects, which found enhancement of intrinsic motivation through verbal rewards, and undermining through tangible rewards, in line with CET. However this analysis did not show any undermining effects for completion-contingent or performance-contingent rewards, and as a result, they called for “abandoning cognitive evaluation theory”.

This was discussed in Deci’s 1999 meta-analysis, and multiple errors were identified and detailed. The authors did not dispute these errors. Nevertheless, contemporary behaviourists are still citing this 1994 paper as as basis for criticisms of CET (e.g. Catania, 2013).

Further Considerations

Rewarding Outcomes vs Behaviours

Recently, there has been an increased interest in rewarding outcomes, rather than behaviour.

Research shows that rewarding outcomes tends to encourage people to take the “shortest path” to that outcome: whatever behaviour is easiest and/or most likely to lead to that outcome.

For example, when rewarded for solving puzzles, participants will choose the easiest puzzles, compared to the choices they make in a free choice scenario.

More disturbingly, people may choose nonconstructive, or immoral, behaviours that lead to the outcome. These behaviours can then be reinforced by the reward. This is sometimes known as the “Enron effect”, but similar effects have been seen with high-stakes testing at schools leading to school administrators cheating, or misreporting results, to achieve the desired outcomes.

We’ll look at this in detail later, but for now, the point is that in order to reliably influence a specific behaviour, a reward must be linked directly to that behaviour. A reward linked to an outcome is likely to lead people to unearth alternative easier behaviours that lead to the rewarded outcome.

Another interesting point is that, although focussing on outcomes rather than process might seem to afford more autonomy, at least within parenting, a focus on outcomes tends to be more associated with controlling parenting styles, which tend to undermine intrinsic motivation. Autonomy-supportive parents tend to be more focussed on learning goals, such as increasing skills or knowledge, rather than measurable performance goals such as grades.

Naturally Occurring Rewards

Not all rewards are provided by an external agent. Some rewards occur naturally, for example exploring a forest, one may find a berry patch.

There is very little empirical study of this kind of reward. However, from a theoretical point of view, this kind of reward does not tend to undermine autonomy, or threaten a person’s I-PLOC, and therefore these kinds of rewards ought not to undermine intrinsic motivation.

Small or “Insufficient” Rewards

Small rewards have less of an undermining effect than larger rewards.

The SDT explanation for this is that small rewards are typically not powerful enough to externally regulate behaviour, and therefore are not typically experienced as controlling.

Furthermore, small rewards (if well used) may signify competence, or have other informational significance (acknowledging information and significance).

Video games are one domain where small rewards often provide acknowledgment and informational feedback, and seem to have positive effects on perceived competence, without any accompanying negative effect on autonomy.

Neuropsychological Support for the Undermining Effect

A 2010 study recreated the undermining effects of rewards, while monitoring brain activity using an fMRI scanner.

Significantly different brain patterns were observed in participants who received expected performance-contingent rewards, vs. unexpected, noncontingent rewards. In the study, participants did a first session of activity under reward conditions (with two groups receiving different types of reward), and a second session of activity for which there were no rewards.

Significant differences in brain activity were seen between the groups in both sessions (even though the second session was identical for both groups), even though in the second session, the two groups were being treated exactly the same. This shows evidence for a persisting effect from the type of reward offered in the first session,

Another study in 2013 has provided support for the idea that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation have quite different underlying mechanisms within the brain.

This is a very new area of research, but further papers seem to be reliably identifying differences in brain activity, corresponding to the phenomenological distinctions made within SDT.

The Undermining Effects of Other External Events

Rewards are not the only mechanism used to motivate people. There have been studies that have looked at the impact of other forms of external influences on intrinsic motivation

Threats of Punishment

CET predicts that threats of punishment would undermine autonomy, and thus have a negative impact on intrinsic motivation.

Perhaps surprisingly, there have been almost no studies of this effect. The only known study was in 1972, and it did show this effect.

Evaluations

A 1987 study in a school context showed that telling children they would be tested on some material they were asked to read reduced their interest in the material.

A 1990 study of Japanese students showed that when comparable feedback was offered in evaluative vs. non-evaluative conditions, the evaluative conditions were found to undermine intrinsic motivation,.

Most studies of evaluation have involved fairly positive evaluations, but still observed undermining effects. The undermining effects will likely be much greater in real-world contexts, where feedback may be more negative, as the recipients of the feedback would not only feel controlled, but also have their sense of competence undermined.

However, this should not be taken to imply that all feedback undermines intrinsic motivation. Informational feedback can enhance intrinsic motivation, and even negative feedback can be given without undermining, as long as it done with support, and to promote efficacy.

Surveillance

Surveillance is not a simple matter - for example the effects of surveillance may be felt very differently if it is invited vs. uninvited.

However most studies so far have shown that surveillance has a negative effect on intrinsic motivation, whether by video or in-person.

Ultimately, the functional significance of the surveillance (i.e. whether it is interpreted by the observed person as supportive, controlling etc.) is likely to determine it’s effect on intrinsic motivation. Later chapters go into more depth on this.

Deadlines and Imposed Goals

Various studies have shown externally-imposed deadlines to diminish intrinsic motivation. This is likely to be due to them undermining participants’ sense of autonomy.

Again, it is the functional significance of deadlines and goals that will determine their effect. In many cases, it is possible to set goals and deadlines with a clear rationale, and in non-controlling ways, such that they can be energizing and potentially motivating.

Later in the book, there is more discussion of how this can be done in a way that supports autonomy, and supports feelings of competence.

Competition: Trying to Win

Competition is often used in sports, games, and the arts to motivate, but what is the nature of the motivation that they generate?

A 1981 compared two groups of puzzle solvers - one was told their goal was to beat another participant the other to complete the puzzle as fast as they could. Both were doing the puzzle head-to-head against another puzzle solver, and both received the same informational feedback that they had completed the puzzle faster than the other puzzle solver.

Those asked to compete subsequently spent less free-choice time playing with the puzzles than those who had not been asked to compete, suggesting that being asked to compete had an undermining effect on intrinsic motivation.

This is interesting, because in SDT, competition should only have a negative impact on intrinsic motivation when it is experienced as controlling. Competition can be highly informational, offering optimal information, and valuable feedback about performance.

Competition turns out to be a complex topic, which will be returned to in chapter 19.

External Events as Supports for Intrinsic Motivation

As well as the potential for external events to undermine intrinsic motivation, it’s also possible for such events to amplify intrinsic motivation.

According to SDT, any event that enhances a person’s sense of volitional engagement in an activity ought to enhance their intrinsic motivation.

Research on Choice

A 1978 study showed that giving participants a choice of which 3 out of 6 puzzles they worked on significantly enhanced their intrinsic motivation.

A 2010 study showed that giving students a choice of homework activity boosted their intrisic motivation, as well as their perception of their competence, their performance on related tests. It also boosted rates of homework completion.

Reeve, Nix and Ham (2003) distinguished between option choice (choosing between options) and action choice (ongoing choices during the activity itself, e.g. what order to do things in, or having the option to switch between activities). Their study showed that action choice was more important than option choice, in supporting an I-PLOC, and enhancing intrinsic motivation. A 2011 study replicated these effects of action choice in the context of PE classes.

A 2008 meta-analysis of 41 studies in this area confirmed this strong connection that providing choice enhances intrinsic motivation.

However it is important to note that providing options is not always motivating - specifically if the options don’t feel like meaningful choices, or there are so many options to choose from that choosing itself becomes burdensome (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000).

The benefits of choice for intrinsic motivation have recently been supported by neurological research using fMRI scans, which again seems to be able to identify specific differences in brain activity that correspond to the observed phenomenological differences.

Perceived Competence: Optimal Challenge and Informational Feedback

Intrinsic motivation is theorized to occur under conditions of optimal challenge. This follows from the idea that the very reason intrinsic motivation exists in humans is to promote our growth (in skills, capabilities etc.).

Where a person has mastered a skill, they may have high rates of success with an activity, but the activity won’t typically provide opportunities for growth. Demonstrating one’s mastery of an activity can yield positive feelings, but these are typically extrinsic pleasures, such as impressing others or reaping the rewards of being skilled in that activity, rather than intrinsic pleasures.

When people are intrinsically motivated, they will tend to choose optimal challenges, but for their intrinsic motivation to be sustained, they must regularly experience mastery. Therefore “optimal challenge” means facing demands that most often one can master - i.e. not far beyond one’s competence, not perpetually on the leading edge of one’s capabilities. High-difficulty challenges can enhance and heighten intrinsic motivation, but only if they occur intermittently.

A 1981 study showed that when children were free to choose their tasks from tasks with a range of difficulties, they spent most time on, and found most interesting, tasks that were just one level ahead of their ability at the start of the experiment.

However, rewarding these children for choosing tasks at this optimal level, resulted in an E-PLOC, and undermined their interest and persistence in these tasks.

Another 1976 study showed that rewarding children for solving puzzles tended to lead to them choosing puzzles that were below their optimal level of challenge.

Overall, the evidence shows that when children are free to select tasks, they select ones that provide optimal challenge, and this in turn maximizes their intrinsic motivation for the tasks.

Feedback Effects (Positive Feedback)

SDT predicts that when a person is working on an activity that provides optimal challenge, positive feedback will typically enhance their intrinsic motivation.

This has been shown in multiple studies from 1984 to 2015.

It is useful to distinguish two types of feedback:

- task-inherent feedback is provided by the task itself, for example as one solves a crossword puzzle, one can see how many clues have been completed, that the letters do / do not fit etc.

- other-mediated feedback is provided by another person observing the task performance. For example, someone training as a psychotherapist won’t receive enough task-inherent feedback to know how they are doing, and will be dependent on feedback from a supervisor.

There is a parallel here with naturally-occurring rewards, vs. administered rewards.

Task-inherent feedback is very likely to be experienced as purely informational, and non-controlling. For other-mediated feedback, the functional significance depends on how the feedback is administered.

in 1982, Ryan showed that providing positive feedback in a controlling way, undermined intrinsic motivation, while equivalent feedback provided in an informational way enhanced intrinsic motivation.

There are complexities to the effects of positive feedback on intrinsic motivation.

- Children may be especially sensitive to the controlling aspects of praise, perhaps because they are used to praise being used to “motivate” them.

- Positive feedback has also been found to be motivating for tasks of optimal challenge, but not for tasks that are too easy

- A 2008 study of participants doing an easy shuttle run found that mild positive feedback was undermining, while strong positive feedback was not.

- Furthermore, it seems that positive feedback can only boost intrinsic motivation when a person experiences an I-PLOC for the activity they are performing.

Nevertheless, despite these complexities, the scientific literature consistently confirms that both perceived autonomy, and perceived competence, predict intrinsic motivation.

In summary, positive feedback mediated by others can boost intrinsic motivation, but only when the communicator has the intention of informing and acknowledging, rather than “motivating” or controlling.

Negative Feedback

Studies have shown that negative feedback tends to consistently undermine intrinsic motivation.

However it seems that in some circumstances, negative feedback can be competence-supportive, rather than merely amotivating.

Theoretically, it seems that a modest amount of negative feedback on an activity, might serve as a challenge, and therefore motivate rather than demotivate. However, from studies conducted so far, there is very little evidence for any effects other than the simple one that negative feedback undermines a person’s sense of competence, and in turn diminishes intrinsic motivation.

How negative feedback is administered is expected to be important too. Negative feedback that pressures or demeans recipients is likely to be strongly demotivating, but negative feedback presented in a more constructive way might not be so problematic. This is an important issue, but there is little research so far that addresses it.

A pair of studies in 2010 and 2013 looked at sports coaches providing constructive and change-oriented feedback. It found that where coaches had an autonomy-supportive (rather than controlling) style, predicted greater intrinsic motivation, well-being, and intention to engage with the sport in the future.

Beyond its impact on intrinsic motivation, negative feedback could also impact extrinsic motivation, by suggesting to them that they do not have control over desired extrinsic outcomes.

Concluding Comments

The key aspects of CET presented in this chapter have been:

- Intrinsic motivation depends on feelings of autonomy and competence

- The impact of external events on intrinsic motivation depends on its functional significance - is it experienced as controlling, or informational?

- We saw how CET can be used to explain a variety of observed effects of different types of rewards, on intrinsic motivation.

- We also saw the effects of a variety of other external events on intrinsic motivation.

The next chapter concludes our presentation of CET, including additional formal propositions. It covers:

- The idea that intra-personal (i.e. internal to the person) events can also be informational or controlling

- An exploration of how the inter-personal climate around behaviour can influence the functional significance of external events (i.e. whether they are perceived as controlling, informational, or amotivating).

Key Concepts from this Chapter

Intrinsic Motivation - Motivation for an activity that is done for the inherent satisfaction gained from the activity, rather than any extrinsic effects that may result from the activity.

“Perceived Locus of Causality” (PLOC) - What a person experiences as their reason for performing an activity. When a person experiences an I-PLOC (Internal Perceived Locus of Causality), they feel that they are acting autonomously. When a person experiences an E-PLOC (External Perceived Locus of Causality), they feel they are being controlled.

Functional Significance - The functional significance of an external stimulus refers to how it is experienced by a person subject to that stimulus. The functional significance of a stimulus may have controlling, informational, or amotivating aspects.

CET Proposition I - Information that supports a persons sense of competence will boost their intrinsic motivation (and the converse also holds).

CET Proposition II - Events that supports a persons sense of autonomy (i.e. contribute to an I-PLOC) will boost intrinsic motivation (and the converse also holds).

CET Proposition III - External events have three aspects, a controlling aspect, an informational aspect, and an amotivating aspect. The interpretation of each event in terms of these aspects will vary depending on the context and the individual, but however the event is interpreted, it will impact intrinsic motivation in line with CET I and CET II.

Rewards commonly have a strong controlling aspect, and therefore often diminish intrinsic motivation. However this is not always the case. The nature of the rewards, how they are administered, and other aspects of context can all affect the functional significance of the reward, and therefore its impact on Intrinsic Motivation.

Other external stimuli including Punishment, Evaluation, Surveillance, Deadlines, Competition, Choice and Feedback can also have significant impacts on Intrinsic Motivation. The impact will depend upon the functional significance of the stimulus, and therefore whether it is experienced as autonomy supporting, or controlling, whether it enhances the person’s experience of competence, and/or whether it has an amotivating aspect.